Editor's note: The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum provided source material to Resource Library for the following article. If you have questions or comments regarding the source material, please contact the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum directly through either this phone number or web address:

In the American Grain: Dove, Hartley, Marin, O'Keeffe, and Stieglitz

September 24, 2004 - January 2, 2005

(above: Georgia O'Keeffe, My Shanty, 1922, oil on canvas. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. )

Building upon the

strengths of The Phillips Collection's (Washington, D.C.) permanent collection,

In the American  Grain: Dove, Hartley, Marin, O'Keeffe, and Stieglitz, will highlight the history of famed collector Duncan Phillips's

acquisition of works by the Stieglitz circle artists and the profound aesthetic

unity of the selections he made. The exhibition, which will explore not

only the work of these inventive artists, but also the relationship between

them and museum founder Duncan Phillips, will open at the Georgia O'Keeffe

Museum, Santa Fe, on September 24, 2004 and will be on view through January

2, 2005. The exhibition is part of an important national tour that provides

a wonderful opportunity to share these works with audiences across the country.

(right: Arthur Dove, Waterfall, 1925, oil on hardboard. The

Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

Grain: Dove, Hartley, Marin, O'Keeffe, and Stieglitz, will highlight the history of famed collector Duncan Phillips's

acquisition of works by the Stieglitz circle artists and the profound aesthetic

unity of the selections he made. The exhibition, which will explore not

only the work of these inventive artists, but also the relationship between

them and museum founder Duncan Phillips, will open at the Georgia O'Keeffe

Museum, Santa Fe, on September 24, 2004 and will be on view through January

2, 2005. The exhibition is part of an important national tour that provides

a wonderful opportunity to share these works with audiences across the country.

(right: Arthur Dove, Waterfall, 1925, oil on hardboard. The

Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

"A large part of our mission is to place Georgia O'Keeffe within a historical context, and to show her work alongside that of her contemporaries," said George G. King, director of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. "This exhibition provides a perfect opportunity to highlight O'Keeffe in this manner and to exhibit some of the best works that were being created by artists of the Stieglitz circle."

According to O'Keeffe Museum curator Barbara Buhler Lynes,

"This is a terrific exhibition in that it not only reveals the innovative

qualities of works by Dove, Hartley, Marin, O'Keeffe, but also how each

artist successfully realized the goal they shared with Stieglitz -- that

of creating an American art whose significance would be considered equal

in importance to that of their European contemporaries." The exhibition

also sheds lights on  Stieglitz's role in shaping the careers of these modernist artists

as well as on the challenges each faced with respect to issues of aesthetics

and patronage at the beginning of the 20th century. (left: Georgia

O'Keeffe, From the White Place, 1940, oil on canvas. The Phillips

Collection, Washington, D.C.)

Stieglitz's role in shaping the careers of these modernist artists

as well as on the challenges each faced with respect to issues of aesthetics

and patronage at the beginning of the 20th century. (left: Georgia

O'Keeffe, From the White Place, 1940, oil on canvas. The Phillips

Collection, Washington, D.C.)

Duncan Phillips first visited Stieglitz's gallery in January 1926. He came to see an exhibition of the work of Dove and went away with three paintings: one by Dove and two by O'Keeffe. In the flurry of correspondence that finalized the arrangements for paying for the paintings and shipping them to Washington, Stieglitz wasted no time in underscoring the idea that would united them for the next 20 years: "What naturally interested me most is your growing interest in the gallant experiment of the living American modernists."

From 1926-46, Phillips acquired the world's largest and most representative group of works by Dove. He also collected characteristic examples of every aspect of Marin's development, and signal works by O'Keeffe, Hartley and Steiglitz. Stieglitz and his artists shared an aesthetic impulse that led them to work from experiences in nature. At a time when European Modernism claimed the attention and patronage of most of the public, these artists attempted to define an independent American art form, invoking mentors from the American past, such as Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman and Ryder.

This exhibition has been organized by The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

ABOUT THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION

The Phillips Collection

founded in 1921, is America's first museum of modern art. Its permanent

collection contains  over 2,400 works by Impressionist and 20th-century modern artists,

as well as Europeans such as Renoir, Bonnard, Matisse, Monet, Degas, Cézanne,

Picasso, Braque and Klee, and Americans such as O'Keeffe, Lawrence, Dove,

Avery, Diebenkorn and Rothko. Housed in the unique setting of the founder's

1897 Georgian Revival home in Washington's Dupont Circle neighborhood, The

Phillips Collection is known for providing visitors with an intimate and

personal connection with some of the world's finest paintings of the late

19th and 20th centuries. (right: Marsden Hartley, Wild Roses,

1942, oil on hardboard. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

over 2,400 works by Impressionist and 20th-century modern artists,

as well as Europeans such as Renoir, Bonnard, Matisse, Monet, Degas, Cézanne,

Picasso, Braque and Klee, and Americans such as O'Keeffe, Lawrence, Dove,

Avery, Diebenkorn and Rothko. Housed in the unique setting of the founder's

1897 Georgian Revival home in Washington's Dupont Circle neighborhood, The

Phillips Collection is known for providing visitors with an intimate and

personal connection with some of the world's finest paintings of the late

19th and 20th centuries. (right: Marsden Hartley, Wild Roses,

1942, oil on hardboard. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

Guided by the vision of its founder -- to bring people together with great works of art -- The Phillips Collection is preparing to undergo an expansion that will add gallery space, improved visitor services, and a Center for Studies in Modern Art. Rather than remove its European Masterworks from public view during this time, The Phillips Collection is sharing them with audiences across the country. A traveling exhibition of 50 of these great works of art, including the beloved Luncheon of the Boating Party, has begun its tour to five American museums, where it is already enjoying great success and critical acclaim. While the new building is under construction, the main Phillips house will remain open, presenting a series of special exhibitions and selections from its permanent collection. The Phillips Collection organizes numerous traveling exhibitions that expand scholarship and, combined with an active lending program, make its works available to audiences throughout the world. The Phillips Collection is a privately supported, non-government institution.

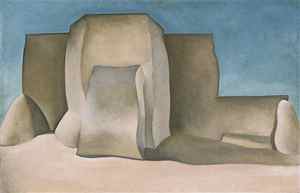

(above: Georgia O'Keeffe, Ranchos Church, Taos, 1929, oil on canvas. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.)

The exhibition will be discussed in three lectures presented by the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum at St. Francis Auditorium, Museum of Fine Arts, 107 West Palace Avenue. Reservations: 505.946.1039:

Following is text from the exhibition visitor's guide:

In January, 1926, Duncan Phillips visited Stieglitz's The Intimate Gallery, New York, for the first time. He had come from Washington, D.C. to see a Dove exhibition and left with one Dove painting and two by O'Keeffe. In the flurry of correspondence that finalized the arrangements for paying for and shipping these work to Phillips, Stieglitz wasted no time in underscoring the idea that united them for the next twenty years: "What naturally interested me most is your growing interest in the gallant experiment of the living American modernists."

Phillips, who had recently founded The Phillips Memorial Art Gallery, Washington, D.C., and the art dealer and artist Stieglitz, met at the crossroads of aesthetics and finance, as dealers and patrons often do. Yet in order for the exchange of art and money to take place between them, Phillips had to see Stieglitz as someone other than a dealer, and Stieglitz, in turn, had to see Phillips as someone other than a patron.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Stieglitz had been the first to promote the avant-garde work of American and European modernists at his first gallery, 291 (1905-17), but by the mid-1920s, had decided to devote his efforts almost exclusively to the promotion of American modern art. Both Stieglitz and Phillips believed they were affecting the course of American society and culture. Stieglitz felt that his artists were producing work whose importance would rival that of work produced by Europeans. He thanked Phillips for his support of Dove, Hartley, Marin, and O'Keeffe by saying that Phillips was "pulling an oar" in "The Cause." Phillips in turn assured Stieglitz that the abiding presence of his artists in Washington would bolster claims for an American art "sown in her own native soil."

From 1926-46, the Stieglitz circle claimed the principal share of commitments Phillips made to living American artists. He acquired the world's largest and most representative group of works by Dove, collected representative examples of every aspect of Marin's oeuvre, and major works by O'Keeffe, Hartley, and Stieglitz. Phillips also enhanced the reputations of Stieglitz's four painters by offering them a number of museum firsts. The Phillips Memorial Art Gallery was the first museum to purchase work by O'Keeffe, to present a solo museum show of Marin's work, and to mount retrospectives of Dove and Hartley.

Less visible to the American public, but most important in Stieglitz's eyes, were the stipends Phillips provided Marin and Dove during the Depression. Dispersing Stieglitz's estate in 1949, Georgia O'Keeffe in effect completed Phillips' collection by donating a set of nineteen cloud photographs by Stieglitz, known as Equivalents. She wrote, "Stieglitz so often spoke of intending to send them himself. I think they will feel very much at home with you."

All of the works in the exhibition are drawn from The Phillips Collection. The exhibition title, In the American Grain, comes from a historical commentary published by William Carlos Williams in 1925.

The Spirit of 291

From 1907-17, 291 was at the center of a community of artists and critics pursuing new discoveries and statements in the arts. Though not specifically defined as an avant-garde movement, the Stieglitz circle raised broad philosophical and aesthetic issues, calling for change in the economics of art, patronage, and the role of the artist in society. 291 was the first American gallery to exhibit the work of Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, and Pablo Picasso, as well as the first to translate and publish excerpts of Wassily Kandinsky's writings on abstraction.

Before World War I, no one could say exactly what lay beyond the breach with tradition. Writing to Stieglitz from Paris in 1913, the photographer and painter Edward Steichen summed up the situation: "One is conscious of unrest and seeking-a weird world hunger for something we evidently haven't got and don't understand. . . . Something is being born or is going to be."

In retrospect Stieglitz commented, "What was 291 but a thinking of America," suggesting that the diverse exhibitions of Rodin, Matisse, African sculpture, Constantin Brancusi, and Picasso were intended as catalysts for a new approach to art and life. What Stieglitz wanted to make clear to his visitors was that he was not only offering ideas and theories about modern culture, but also the opportunity to define it in twentieth century America.

The Stieglitz Circle

Marin, Dove, Hartley, and O'Keeffe were connected personally and aesthetically with Stieglitz for almost forty years. All had gravitated to 291 during their formative years at the beginning of the century. Exposed to the revolutionary art shown there and discussed in Camera Work, the magazine Stieglitz published from 1903-17, these painters renounced outmoded conventions and became convinced that abstract forms could communicate feelings and ideas. Stieglitz welcomed these young Americans, admired their creative vitality, and exhibited their works regularly. Equally important, he aligned his own art with their subjects.

After World War I Stieglitz and his painters shared an aesthetic impulse-what William Carlos Williams called a desire for "contact"-that led them to work from their own experiences in nature. At a time when European modernism claimed most public attention and patronage, they began defining an independent American art form invoking mentors such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, and Albert Pinkham Ryder. Working in regions as diverse as New York, Maine, and New Mexico, Stieglitz's artists redefined the parameters of American art as well as the technical possibilities of their respective mediums. Native surroundings and local experience became measures of authenticity for them. As Williams proposed, "Take anything, the land at your feet, and use it."

Stieglitz affirmed his commitment to his four painters through numerous, well-orchestrated exhibitions at his galleries, The Intimate Gallery and An American Place, that opened in New York in 1925 and 1929 respectively. Through his promotion of their work-art that Stieglitz called "new America" in the making-he questioned the success of European art that represented the commercialism and conventionalism he had always abhorred. He also enlisted American writers such as Williams, Sherwood Anderson, Waldo Frank, and Paul Rosenfeld to speak out on his behalf. Until his death in 1946, Stieglitz welcomed all visitors to his galleries in hopes of finding individuals who shared his dreams about American modernist art.

Arthur Dove (1880-1946)

Arthur Dove was arguably the first American modernist to embrace abstraction in 1910, the year his work was first exhibited at 291. In the 1920s, while living on a houseboat in Huntington Harbor, Dove returned to the world of objects in a series of lyrical collages. Later he focused upon more traditional landscape subjects surrounding his childhood home in Geneva, New York. In the 1930s and 1940s, Dove continued to test unorthodox materials, as well as new colors in wax emulsion, exploring and displaying an amazing stylistic and technical range. His surging diagonals and repeating, radiating forms suggest forces of growth and decay in nature that evoke remarkable comparisons with the works of Stieglitz and O'Keeffe. Both Dove and Stieglitz believed O'Keeffe's emotionally direct painting had set a standard to follow. Upon seeing her work for the first time in 1916, Dove praised O'Keeffe for "doing naturally what many of us fellows are trying to do and failing." O'Keeffe later praised Dove for being "the only American painter who is of the earth."

Marsden Hartley (1877-1943)

Stieglitz first exhibited Hartley's work at 291 in 1909--a series of landscapes painted in Maine. In 1912, Hartley went to Paris and became aware of Kandinsky's Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1910) and Der Blaue Reiter (1912), the almanac published by German expressionist artists. As the first Stieglitz circle artist to read Kandinsky, Hartley sent news of his discovery to Stieglitz and related his understanding of how Kandinsky' ideas were similar to those of Emerson and Whitman. He also began working abstractly in an effort to actualize components of Kandinsky's theories, or as Hartley put it: to convey the "sensation of cosmic bodies in harmony with each other by means of color & form." In the 1920s, when Stieglitz was touting O'Keeffe's independence from European sources, Hartley was living mostly in Berlin and France painting still lifes inspired by Georges Braque and Juan Gris, landscapes of New Mexico from memory, and a series of Cézanne inspired landscapes of Provence. In March 1930, at Stieglitz's urging, Hartley returned to America, settling permanently in Maine in the summer of 1937. Characterized by bold primary colors and strongly outlined shapes, Hartley's late work expressed profound emotions that resonated in the haunting seascapes and mountains of his home state.

John Marin (1870-1953)

Stieglitz and Marin met in Paris in 1909. Stieglitz was known internationally for his work in photography and Marin as a superb draftsman and a master watercolorist. While in Paris and highly influenced by the work of Cubist artists, Marin created a series of radical works using vigorous strokes of paint through which he explored and expressed his changing moods and responses to the world around him. Upon returning to New York, he was one of the first American artists to capture in his work both the tempo and pace of the city of New York. After 1920 he spent summers in Maine, sharing Hartley's attraction to the northern ocean, but the staccato cubist rhythms of his Maine-inspired works differ markedly from the weighty, brooding forms in paintings Hartley made there.

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986)

On New Year's Day 1916, Alfred Stieglitz first saw Georgia O'Keeffe's work -- a series of remarkable charcoal abstractions. Her drawings seemed utterly new to him and free of any influence from Europe. Stieglitz featured ten of these drawings in a group exhibition at 291 that spring and, in the spring of 1917, closed the doors of his famous gallery with a solo exhibition of O'Keeffe's work. Thereafter, O'Keeffe was the central focus of his life (they married in 1924), and beginning in 1918 they began spending winter and spring in New York and summer and fall at Stieglitz's family property at Lake George in the Adirondacks. This pattern continued until 1929, when O'Keeffe began spending summers painting in New Mexico. In the 1920s, O'Keeffe redefined herself as a representational painter especially through her large-scale iconic images of cropped floral forms seen close-up in a shallow almost photographic depth of field and as if observed through a magnifying lens. Her New Mexico paintings present subjects that capture with seeming realism the character and beauty of the area's architectural and landscape forms. But through their abstract underpinnings O'Keeffe continued to explore her fascination with abstraction to which she returned almost exclusively by the late 1950s. She made New Mexico her permanent home three years after Stieglitz's death in 1946.

Editor's note: RL readers may also enjoy these earlier articles concerning this traveling exhibition:

Read more articles and essays concerning this institutional source by visiting the sub-index page for the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Resource Library.

For further biographical information on selected artists cited in this article please see America's Distinguished Artists, a national registry of historic artists.

rev. 9/27/04, 9/10/10

Search Resource Library for thousands of articles and essays on American art.

Copyright 2010 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights reserved.