Online Video - Creating new programming

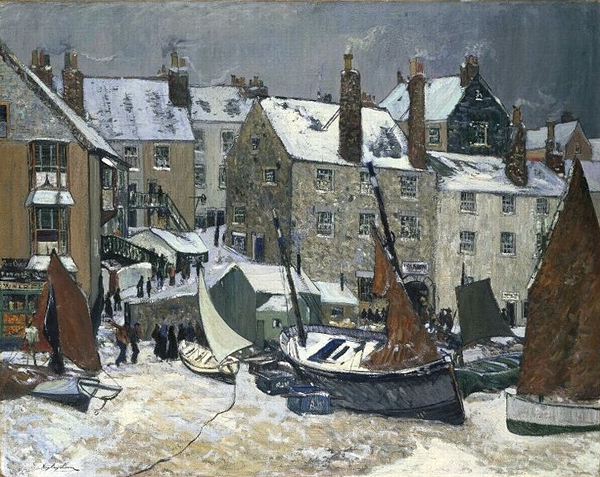

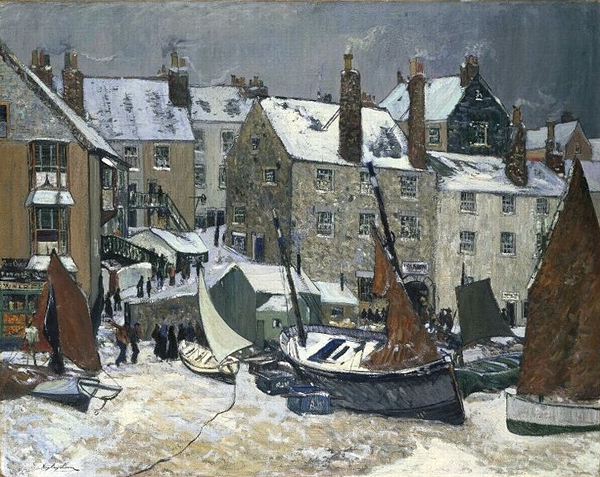

(above: Richard Hayley Lever, Winter, St. Ives, c. 1914, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches, Brooklyn Museum, Caroline H. Polhemus Fund. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons*)

Technical considerations:

Marc Bretzfelder of Smithsonian TV spoke with TFAO in April 2005 and shared tips on employing video to record lectures. Marc said that to produce an engaging video the production should emulate the way the an individual experiences a live event such as a lecture accompanied by slides. A viewer in the audience typically looks at the speaker until a new slide is projected. Then the viewer looks at the slide long enough to capture the information from the slide. After the slide content is absorbed, the viewer shifts attention back to the speaker until the next slide is presented or the lecturer points out a detail within the slide.

To enable a recording of slide lectures mimicking the viewer's live experience, Marc found that simultaneously using two cameras with live mixing is sufficient. One camera is focused on the speaker and the other camera has locked focus on, and white balance set for, the screen where the slides will be shown. Live mixing is used to switch between the lecturer and the screen. The two camera, switcher, record deck configuration can be successfully managed by one person with experience using video equipment.

For equipment, he recommended the purchase of two high

quality digital cameras in the $2,500 per camera price range.[1] In addition,

a video mixer ($2,500  - $3,000 price range) is needed

such as the MX-Pro DV by Videonics, [2] providing firewire input and output.

Also, a $300 consumer video camera is required to act as a record deck,

capturing the mixed video produced by the video switcher. After the taping,

the tape is encoded and streamed by Smithsonian TV. Marc said that a producer

may additionally wish to concurrently make a DVD -- alongside the taping

-- with a $250-350 consumer quality recorder. He found that lecturers appreciate

the courtesy of receiving a copy of a DVD made of the lecture. (right: image

of MX-Pro DV by Videonics)

- $3,000 price range) is needed

such as the MX-Pro DV by Videonics, [2] providing firewire input and output.

Also, a $300 consumer video camera is required to act as a record deck,

capturing the mixed video produced by the video switcher. After the taping,

the tape is encoded and streamed by Smithsonian TV. Marc said that a producer

may additionally wish to concurrently make a DVD -- alongside the taping

-- with a $250-350 consumer quality recorder. He found that lecturers appreciate

the courtesy of receiving a copy of a DVD made of the lecture. (right: image

of MX-Pro DV by Videonics)

Mixing is performed live, avoiding post production time. Audio input is provided by the staff operating the sound system in the lecture hall.[3] Marc found that using illustrated audio (synchronizing digital slide images with sound clips) takes about 4 hours of post-production editing to every hour of lecture time, which discourages staff from using the illustrated audio approach.

From time to time Marc coaches staff from individual Smithsonian museums how to record lectures and provides suggestions to them on equipment needed. [4]

Example of a Smithsonian TV dual camera video:

On November 10, 2004 Alexander Nemerov gave a one hour illustrated slide lecture titled "Childhood Imagination:The Case of N. C. Wyeth and Robert Louis Stevenson." This lecture was part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Clarice Smith Lecture Series. Dr. Nemerov is professor of art history at Yale University. He has written extensively on American art history, including the books Frederic Remington and Turn-of-the-Century America and The Body of Raphaelle Peale: Still Life and Selfhood, 18121824.

Notes:

1. According to cnet.com a business-quality

digital camcorder of sufficient quality to record lectures should have these

features:

1. According to cnet.com a business-quality

digital camcorder of sufficient quality to record lectures should have these

features:

An example of a camcorder with these features is the Panasonic AG-DVX100A, shown above left.

Due to the advent of HDTV, museums may

wish to purchase HD camcorders featuring wide-aspect viewing. These camcorders

let museums capture widescreen (16:9) high-definition (HDV 720p and 1080i)

video, offering superb video, with unprecedented clarity, color quality

and image detail. (left: image of entry level Sony HDR-FX1 high definition

camcorder with three-chip HD images; native 16:9 capture, which offers recording

of high-definition video on MiniDV cassettes )

Due to the advent of HDTV, museums may

wish to purchase HD camcorders featuring wide-aspect viewing. These camcorders

let museums capture widescreen (16:9) high-definition (HDV 720p and 1080i)

video, offering superb video, with unprecedented clarity, color quality

and image detail. (left: image of entry level Sony HDR-FX1 high definition

camcorder with three-chip HD images; native 16:9 capture, which offers recording

of high-definition video on MiniDV cassettes )

HD can be edited by software such as iMovie HD from Apple Computer. iMovie HD supports MPEG-4, iSight, Widescreen, and DV. Videographers have advised TFAO that rendering raw HD tapes into other formats is more time consuming and difficult than working with a standard definition tape.

2. Smithsonian TV's Marc Bretzfelder advises that there is an upgrade mixer available, the MX-4 DV, which "has the benefit of allowing up to 12 simultaneous inputs, 4 DV, 4 S-Video and 4 composite. It still has the same small and portable form factor. It also will accept and store jpegs, allowing one to preproduce Opening Titles and credits, and probably superimpose speaker's names, but I am not certain about that."

3. If audio is not supplied by the lecture hall or if video is being shot elsewhere, care needs to be taken in producing acceptable audio quality. C/net's camcorder buying guide has a relevant section titled "How do I get good sound."

4. In TFAO's examples of online

video, improper lighting has often resulted in poor picture quality.

Care must be taken to position lighting for acceptable results. In auditoriums

being used for slide show lectures, ambient lighting can dull projected

images. Ways of reducing this effect include: placement of screen as far

as possible from an illuminated lectern,  illuminating

the lectern only when camera is switched to speaker, and placement of screen

in front of lectern. Endorphin Productions provides these examples of adequate

lighting: (right: Smith Victor KT900 3-Light 1250-Watt Thrifty Mini-Boom

Kit with Light Cart on Wheels Carrying Case)

illuminating

the lectern only when camera is switched to speaker, and placement of screen

in front of lectern. Endorphin Productions provides these examples of adequate

lighting: (right: Smith Victor KT900 3-Light 1250-Watt Thrifty Mini-Boom

Kit with Light Cart on Wheels Carrying Case)

Another way of achieving high quality online renditions of art being shown on a movie screen is explained in TFAO's Project Checklist. Insertion of still images during scene editing may produce a much better rendition of on-screen images than achievable through filming the screen itself.

(above: Frank Xavier Leyendecker, The Flapper, Life Magazine cover, 2 February, 1922. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons*)

Go to:

Go back to introduction for Creating new programming

rev. 9/22/05

Links to sources of information

outside of our web site are provided only as referrals for your further

consideration. Please use due diligence in judging the quality of information

contained in these and all other web sites. Information from linked sources

may be inaccurate or out of date. TFAO neither recommends or endorses these

referenced organizations. Although TFAO includes links to other web sites,

it takes no responsibility for the content or information contained on those

other sites, nor exerts any editorial or other control over them. For more

information on evaluating web pages see TFAO's General Resources section in Online Resources for Collectors and Students of

Art History.

*Tag for expired US copyright of object image:

Search Resource Library

Search Resource Library

Copyright 2022 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights reserved.